The “Service Flow-print:” A Proposed Artifact for Complex Service Designs

This post is an adaptation of a pecha kucha talk I gave to the DC chapter of the Service Design Network for its celebration of Service Design Day. A recording of the talk is on YouTube. It was originally published on Forum One’s site in July, 2000.

The Problem: A Great Tool That Doesn’t Always Work

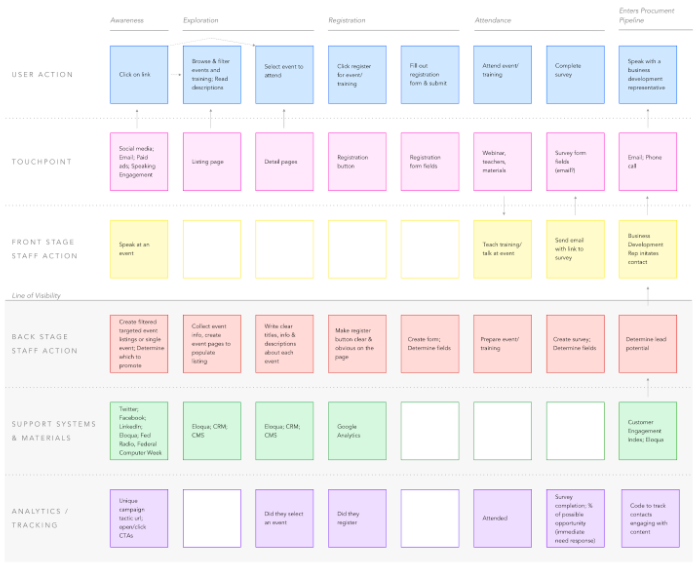

When I began exploring the experience design variations emerging in the service design space a few years ago, one tool particularly attracted my attention: the service blueprint. My colleague Julia Bradshaw wrote a great introduction to these artifacts last year; in summary, they concisely diagram all the facets involved in providing a service to end customers. Here’s an example:

Each column is a step in the service delivery process, but what is unique and powerful is the rows - “swimlanes” - because they show clearly that providing the service involves people, systems, AND the processes, all working together. They also emphasize that, while there are key customer-facing activities - the “front stage” - the service can’t happen without actions happening behind the scenes - the “back stage.” It is critical to be forced to think about all these elements as one considers the design of an experience.

A current project I am leading with the US Department of Health & Human Services’ Office of Head Start (OHS) seemed the perfect use case for a service blueprint. We had completed an array of research activities to understand one of OHS’s key services we needed to pull together our findings for review and subsequent design work. Here, however, we ran into a problem.

If you study the example above, it might strike you that the service blueprint has a major weakness: it is purely linear. It relies on the underlying service process to be a smooth ‘first A, the B, then C’ flow with no consequential forks or decision points. The service I was documenting didn’t look at all like that, though. We were trying to document important alternate paths and inconsistently used flows. A service blueprint just wouldn’t work.

The Solution: A Marriage of Artifacts

The classic way to document complex complex processes is the flow chart. Done right, these tools can show divergent and alternate paths and their various outcomes. They don’t, however, include all the valuable information in the swim lanes of a service blueprint. What was needed, I realized, is to marry the depth of a service blueprint onto the process layout of a flow diagram. Behold: the “service flow-print.”

The “flow-print” has, at its core, a simplified flow chart. I use standard symbols for initiations and endings, steps, and decision points.

What’s different is that I add much more information to the boxes for each step; they aren’t just brief labels.

Remember the swimlanes from the service blueprint? The “service flow-print” integrates them into each step of the process, as is appropriate. Here’s the same piece of the whole, all filled in:

Each color represents a different swimlane, and the order and structure is fixed:

There are some deliberate, important choices I made in designing the tool:

The audience, represented by yellow, appears in every box, even if it is only an empty, yellow-outlined box to indicate there is no audience interaction in that step. I wanted there to be continuity and a clear reminder of when the audience is and is not involved. Note that it may be entirely appropriate for audiences not to be involved in a step, but I wanted to provoke deliberate thought on this point.

On a traditional service blueprint, the Line of Visibility, the line that separates the audience-facing front-stage and the internal-facing back stage is a clear marker that runs across the document horizontally. In my diagram, that clear horizontal line doesn’t work, but I retain it by placing an indicator in each and every box, even for cases where there are only front stage or only back stage activities. This creates an anchor to orient the reader and emphasize the two states.

Our research turned up several general principles or business rules that governed how OHS operated the service in question. These were important to capture, so I created a separate back stage swim lane for them, distinct from the people and technology elements.

The diagram alone gives some information, but to make it clear where to focus, I added an additional layer that marks places where the research uncovered issues, inconsistencies, or areas we’d like to know more about.

We created a companion slide deck to provide detail on all these points. Make sure you capture the source research well so you can point back to it. We didn’t want to attribute comments directly, but we did pair the facts we documented above with quotes, and, in the case of usability tests, videos, to give emotional weight to our points. You have to tell the full story to make the case for subsequent changes.

What’s Next? How Will We Use This New Tool?

We are now using the tool to prioritize the areas on which we need to focus first. Being able to see the whole service, and see where dependencies and points of leverage are will be important in this task. We will also be able to identify who needs to be involved - or who needs serious buy-in for change - not only by looking directly at the swimlanes in the immediate steps, but also by looking “downstream” at others who may become involved or interested later. It is clearly just one tool we’ll need - direct workshops to generate ideas for solutions will be key - but it will certainly help focus us and move our efforts to improve the performance of this OHS service.